PHAROS

THE

EGYPTIAN

BY GUY BOOTHBY.

Illustrated by JOHN H. BACON

SYNOPSIS OF FOREGOING CHAPTERS.

| August | Contents | October |

Illustrated by JOHN H. BACON

SYNOPSIS OF FOREGOING CHAPTERS.

|

As soon as we were at anchor, and the necessary formalities of the port had been complied with, Pharos's servant, the man who had accompanied us from Pompeii and who had brought me on board in Naples, made his way ashore, whence he returned in something less than an hour to inform us that he had arranged for a special train to convey us to our destination. We accordingly bade farewell to the yacht and were driven to the railway-station, a primitive building on the outskirts of the town. Here an engine and a single carriage awaited us. We took our places, and five minutes later were steaming across the flat, sandy plain that borders the Canal and separates it from the Bitter Lakes.

Ever since the storm, and the unpleasant insight it had afforded me into Pharos's character, our relations had been somewhat strained. As the Fräulein Valerie had predicted, as soon as he recovered his self-possession he hated me the more for having been a witness of his cowardice. For the remainder of the voyage he scarcely put in an appearance on deck, but spent the greater portion of his time in his own cabin, though in what manner he occupied himself there I could not imagine.

Now that we were in our railway-carriage, en route to Cairo, looking out upon that dreary landscape, with its dull expanse of water on one side, and the high bank of the Canal, with, occasionally, glimpses of the passing stations, on the other, we were brought into actual contact, and, in consequence, things improved somewhat. But even then we could scarcely have been described as a happy party. The Fräulein Valerie sat for the most part silent and preoccupied, facing the engine in the right-hand corner; Pharos, wrapped in his heavy fur coat and rug, and with his inevitable companion cuddled up beside him, had taken his place opposite her. I sat in the farther corner, watching them both, and dimly wondering at the strangeness of my position. At Ismailya another train awaited us, and when we and our luggage had been transhipped to it we continued our journey, entering now on the region of the desert proper. The heat was almost unbearable, and to make matters worse, as soon as darkness fell and the lamps were lighted, swarms of mosquitoes emerged from their hiding-places and descended upon us. The train rolled and jolted its way over the sandy plain, passed the battlefields of Tel-el-Kebir and Kassassin, and still Pharos and the woman opposite him remained seated in the same position, he with his head thrown back, and the same deathlike expression upon his face, and she, staring out of the window, but, I am certain, seeing nothing of the country through which we were passing. It was long after midnight when we reached the capital. Once more the same obsequious servant was in attendance. A carriage, he informed us, awaited our arrival at the station door, and in it we were whirled off to the hotel, at which rooms had been engaged for us. However disagreeable Pharos might make himself, it was at least certain that to travel with him was to do so in luxury.

Of all the impressions I received that day, none struck me with greater force than the drive from the station to the hotel. I had expected to find a typical Eastern city; in place of it I was confronted with one that was almost Parisian, as far as its handsome houses and broad, tree-shaded streets were concerned. Nor was our hotel behind it in point of interest. It proved to be a gigantic affair, elaborately decorated in the Egyptian fashion, and replete, as the advertisements say, with every modem convenience. The owner himself met us at the entrance, and from the fact that he informed Pharos, with the greatest possible respect, that his old suite of rooms had been retained for him, I gathered that they were not strangers to each other.

"At last we are in Cairo, Mr. Forrester," said the latter with an ugly sneer, when we had reached our sitting-room, in which a meal had been prepared for us, "and the dream of your life is realized. I hasten to offer you my congratulations."

In my own mind I had a doubt as to whether it was a matter of congratulation to me to be there in his company. I, however, made an appropriate reply, and then assisted the Fräulein Valerie to divest herself of her travelling cloak. When she had done so, we sat down to our meal. The long railway journey had made us hungry; but, though I happened to know that he had tasted nothing for more than eight hours, Pharos would not join us. As soon as we had finished, we bade each other good-night and retired to our various apartments.

On reaching my room, I threw open my window and looked out. I could scarcely believe that I was in the place in which my father had taken such delight, and where he had spent so many of the happiest hours of his life.

When I woke, my first thought was to study the city from my bedroom window. It was an exquisite morning, and the scene before me more than equalled it in beauty. From where I stood I looked away across the flat roofs of houses, over the crests of palm trees, into the blue distance beyond, where, to my delight, I could just discern the Pyramids peering up above the Nile. In the street below, stalwart Arabs, donkey boys, and almost every variety of beggar could be seen; and while I watched, emblematical of the change in the administration of the country, a guard of Highlanders, with a piper playing at their head, marched by, en route to the headquarters of the Army of Occupation.

As usual, Pharos did not put in an appearance when breakfast was served. Accordingly, the Fräulein and I sat down to it alone. When we had finished, we made our way to the cool stone verandah, where we seated ourselves, and I obtained permission to smoke a cigarette. That my companion had something upon her mind, I was morally convinced. She appeared nervous and ill at ease, and I noticed that more than once, when I addressed some remark to her, she glanced eagerly at my face, as if she hoped to obtain an opening for what she wanted to say, and then, finding that I was only commenting on the stateliness of some Arab passer-by, the beautiful peep of blue sky permitted us between two white buildings opposite, or the graceful foliage of a palm overhanging a neighbouring wall, she would heave a sigh and turn impatiently from me again.

"Mr. Forrester," she said at last, when she could bear it no longer, "I intended to have spoken to you yesterday, but I was not vouchsafed an opportunity. You told me on board the yacht that there was nothing you would not do to help me. I have a favour to ask of you now. Will you grant it?"

Guessing from her earnestness what was coming, I hesitated before I replied.

"Would it not be better to leave it to my honour to do or not to do so after you have told me what it is?" I asked.

"No; you must give me your promise first," she replied. "Believe me, I mean it when I say that your compliance with my request will make me a happier woman than I have been for some time past." Here she blushed a rosy red, as though she thought she had said too much. "But it is possible my happiness does not weigh with you."

"It weighs very heavily," I replied. "It is on that account I cannot give my promise blindfold."

On hearing this, she seemed somewhat disappointed.

"I did not think you would refuse me," she said, "since what I am going to ask of you is only for your own good. Mr. Forrester, you have seen something on board the yacht of the risk you run while you are associated with Pharos. You are now on land again, and your own master. If you desire to please me, you will take the opportunity and go away. Every hour that you remain here only adds to your danger. The crisis will soon come, and then you will find that you have neglected my warning too long."

"Forgive me," I answered, this time as seriously as even she could desire, "if I say that I have not neglected your warning. Since you have so often pointed it out to me, and judging from what I have already seen of the character of the old gentleman in question, I can quite believe that he is capable of any villainy; but, if you will pardon my reminding you of it, I think you have heard my decision before. I am willing, nay, even eager to go away, provided you will do the same. If, however, you decline, then I remain. More than that I will not, and less than that I cannot, promise."

"What you ask is impossible; it is out of the question," she continued. "As I have told you so often before, Mr. Forrester, I am bound to him for ever, and by chains that no human power can break. What is more, even if I were to do as you wish, it would be useless. The instant he wanted me, if he were thousands of miles away and only breathed my name, I should forget your kindness, my freedom, his old cruelty—everything, in fact—and go back to him. Have you not seen enough of us to know that where he is concerned, I have no will of my own? Besides —but there, I cannot tell you any more! Let it suffice that I cannot do as you ask."

Remembering the interview I had overheard that night on board the yacht, I did not know what to say. That Pharos had her under his influence, I had, as she had said, seen enough to be convinced. And yet, regarded in the light of our sober, every-day life, how impossible it all seemed! I looked at the beautiful, fashionably-dressed woman seated by my side, playing with the silver handle of her Parisian parasol, and wondered if I could be dreaming, and whether I should presently waken to find myself in bed in my comfortable rooms in London once more, and my servant entering with my shaving water.

"I think you are very cruel!" she said, when I returned no answer. "Surely you must be aware how much it adds to my unhappiness to know that another is being drawn into his toils, and yet you refuse to do the one and only thing which can make my mind easier."

"Fräulein," I said, rising and standing before her, "the first time I saw you I knew that you were unhappy. I could see that the canker of some great sorrow was eating into your heart. I wished that I could help you, and Fate accordingly willed that I should make your acquaintance. Afterwards, by a terrible series of coincidences, I was brought into personal contact with your life. I found that my first impression was a correct one. You were miserable, as, thank God! few human beings are. On the night that I dined with you in Naples you warned me of the risk I was running in associating with Pharos, and implored me to save myself. When I knew that you were bound hand and foot to him, can you wonder that I declined? Since then I have been permitted further opportunities of seeing what your life with him is like. Once more you ask me to save myself, and once more I make you this answer. If you will accompany me, I will go; and if you do so, I swear to God that I will protect and shield you to the best of my ability. I have many influential friends who will count it an honour to take you into their families until something can be arranged, and with whom you will be safe. On the other hand, if you will not go, I pledge you my word that so long as you remain in this man's company I will do so too. No argument will shake my determination, and no entreaty move me from the position I have taken up."

I searched her face for some sign of acquiescence, but could find none. It was bloodless in its pallor, and yet so beautiful, that at any other time and in any other place I should have been compelled by the love I felt for her—a love that I now knew to be stronger than life itself—to take her in my arms and tell her that she was the only woman in the wide world for me, that I would protect her, not only against Pharos, but against his master, Apollyon himself. Now, however, such a confession was impossible. Situated as we were, hemmed in by dangers on every side, to speak of love to her would have been little better than an insult.

"What answer do you give me?" I said, seeing that she did not speak.

"Only that you are cruel," she replied. "You know my misery, and yet you add to it. Have I not told you that I should be a happier woman if you went?"

"You must forgive me for saying so, but I do not believe it," I said, with a boldness and a vanity that surprised even myself. "No, Fräulein, do not let us play at cross purposes. It is evident you are afraid of this man, and that you believe yourself to be in his power. I feel convinced it is not as bad as you say. Look at it in a matter-of-fact light and tell me how it can be so? Supposing you leave him now, and we fly, shall we say, to London. You are your own mistress and quite at liberty to go. At any rate, you are not his property to do with as he likes, so if he follows you and persists in annoying you, there are many ways of inducing him to refrain from doing so."

She shook her head.

"Once more, I say, how little you know him, Mr. Forrester, and how poorly you estimate his powers! Since you have forced me to it, let me tell you that I have twice tried to do what you propose. Once in St. Petersburg and once in Norway. He had terrified me, and I swore that I would rather die than see his face again. Almost starving, supporting myself as best I could by my music, I made my way to Moscow, thence to Kiev and Lemburg and across the Carpathians to Buda-Pesth. Some old friends of my father's, to whom I was ultimately forced to appeal, took me in. I remained with them a month, and during that time heard nothing either of or from Monsieur Pharos. Then, one night, when I sat alone in my bedroom, after my friends had retired to rest, a strange feeling that I was not alone in the room came over me—a feeling that something, I do not know what, was standing behind me, urging me to leave the house and to go out into the wood which adjoined it to meet the man whom I feared more than poverty, more than starvation, more even than death itself. Unable to refuse, or even to argue with myself, I rose, drew a cloak about my shoulders, and, descending the stairs, unbarred a door and went swiftly down the path towards the dark wood to which I have just referred. Incredible as it may seem, I had not been deceived. Pharos was there, seated on a fallen tree, waiting for me."

"Once more, I say, how little you know him, Mr. Forrester, and how poorly you estimate his powers! Since you have forced me to it, let me tell you that I have twice tried to do what you propose. Once in St. Petersburg and once in Norway. He had terrified me, and I swore that I would rather die than see his face again. Almost starving, supporting myself as best I could by my music, I made my way to Moscow, thence to Kiev and Lemburg and across the Carpathians to Buda-Pesth. Some old friends of my father's, to whom I was ultimately forced to appeal, took me in. I remained with them a month, and during that time heard nothing either of or from Monsieur Pharos. Then, one night, when I sat alone in my bedroom, after my friends had retired to rest, a strange feeling that I was not alone in the room came over me—a feeling that something, I do not know what, was standing behind me, urging me to leave the house and to go out into the wood which adjoined it to meet the man whom I feared more than poverty, more than starvation, more even than death itself. Unable to refuse, or even to argue with myself, I rose, drew a cloak about my shoulders, and, descending the stairs, unbarred a door and went swiftly down the path towards the dark wood to which I have just referred. Incredible as it may seem, I had not been deceived. Pharos was there, seated on a fallen tree, waiting for me."

"And the result?"

"The result was that I never returned to the house, nor have I any recollection of what happened at our interview. The next thing I remember was finding myself in Paris. Months afterwards I learnt that my friends had searched high and low for me in vain, and had at last come to the conclusion that my melancholy had induced me to make away with myself. I wrote to them to say that I was safe, and to ask their forgiveness, but my letter has never been answered. The next time was in Norway. While we were there, a young Norwegian pianist came under the spell of Pharos's influence. But the load of misery he was called upon to bear was too much for him, and he killed himself. In one of his cruel moments Pharos congratulated me on the success with which I had acted as his decoy. Realising the part I had unconsciously played, and knowing that escape in any other direction was impossible, I resolved to follow the wretched lad's example. I arranged everything as carefully as a desperate woman could do. We were staying at the time near one of the deepest fjords, and if I could only reach the place unseen, I was prepared to throw myself over into the water five hundred feet below. Every preparation was made, and when I thought Pharos was asleep, I crept from the house and made my way along the rough mountain path to the spot where I was going to say farewell to my wretched life for good and all. For days past I had been nerving myself for the deed. Reaching the spot, I stood upon the brink, gazing down into the depths below, thinking of my poor father, whom I expected soon to join, and wondering when my mangled body would be found. Then, lifting my arms above my head, I was about to let myself go, when a voice behind me ordered me to stop. I recognised it, and though I knew that before he could approach me it was possible for me to effect my purpose, and place myself beyond even his power for ever, I was unable to do as I desired.

"'Come here,' he said,—and since you know him you can imagine how he would say it,—' this is the second time you have endeavoured to outwit me. First you sought refuge in flight, but I brought you back. Now you have tried suicide, but once more I have defeated you. Learn this, that as in life so even in death you are mine to do with as I will.' After that he led me back to the hotel, and from that time I have been convinced that nothing can release me from the chains that bind me."

Once more I thought of the conversation I had overheard through the saloon skylight on board the yacht. What comfort to give her, or what answer to make, I did not know. I was still debating this in my mind when she rose, and, offering some excuse, left me and went into the house. When she had gone, I seated myself in my chair again and tried to think out what she had told me. It seemed impossible that her story could be true, and yet I knew her well enough by this time to feel sure that she would not lie to me. But for such a man as Pharos to exist in this prosaic nineteenth century, and stranger still, for me, Cyril Forrester, who had. always prided myself on my clearness of head, to believe in him, was absurd. That I was beginning to do so was, in a certain sense, only too true. I was resolved, however, that, happen what might in the future, I would keep my wits about me and endeavour to outwit him, not only for my own sake, but for that of the woman I loved, whom I could not induce to seek refuge in flight while she had the opportunity.

During the afternoon I saw nothing of Pharos. He kept himself closely shut up in his own apartment, and was seen only by that same impassive manservant I have elsewhere described. The day, however, was not destined to go by without my coming in contact with him. The Fräulein Valerie and I had spent the evening in the cool hall of the hotel, but being tired she had bidden me good-night and gone to her room at an early hour. Scarcely knowing what to do with myself, I was making my way upstairs to my room, when the door of Pharos's apartment opened, and to my surprise the old man emerged. He was dressed for going out—that is to say, he wore his long fur coat and curious cap. On seeing him, I stepped back into the shadow of the doorway, and was fortunate enough to be able to do so before he became aware of my presence. As soon as he had passed, I went to the balustrading and watched him go down the stairs, wondering, as I did so, what was taking him from home at such a late hour. The more I thought of it the more inquisitive I became. A great temptation seized me to follow him and find out. Being unable to resist it, I went to my room, found my hat, slipped a revolver into my pocket, in case I might want it, and set off after him.

On reaching the great hall, I was just in time to see him step into a carriage, which had evidently been ordered for him beforehand. The driver cracked his whip, the horses started off, and, by the time I stood in the porch, the carriage was a good distance down the street.

"Has my friend gone?" I cried to the porter, as if I had hastened downstairs in the hope of seeing him before he left. "I had changed my mind and intended accompanying him. Call me a cab as quickly as you can."

One of the neat little victorias which ply in the streets of Cairo was immediately forthcoming, and into it I sprang.

"Tell the man to follow the other carriage," I said to the porter, "as fast as he can go."

The porter said something in Arabic to the driver, and a moment later we were off in pursuit.

It was a beautiful night, and, after the heat of the day, the rush through the cool air was infinitely refreshing. It was not until we had gone upwards of a mile, and the first excitement of the chase had a little abated, that the folly of what I was doing came home to me, but even then it did not induce me to turn back. Connected with Pharos as I was, I was determined, if possible, to find out something more about him and his doings before I permitted him to get a firmer hold upon me. If I could only discover his business on this particular night, it struck me, I might know how to deal with him. I accordingly pocketed my scruples, and slipping my hand into my pocket to make sure that my revolver was there, I permitted my driver to proceed upon his way unhindered. By this time we had passed the Kasr-en-nil Barracks, and were rattling over the great Nile Bridge. It was plain from this that, whatever the errand might be that was taking him abroad, it at least had no connection with old Cairo.

Crossing the Island of Bulak, and leaving the caravan depot on our left, we headed away under the avenue of beautiful Lebbek trees along the road to Gizeh. At first I thought it must be the museum he was aiming for, but this idea was dispelled when we passed the great gates and turned sharp to the right hand. Holding my watch to the carriage-lamp, I discovered that it wanted only a few minutes to eleven o'clock.

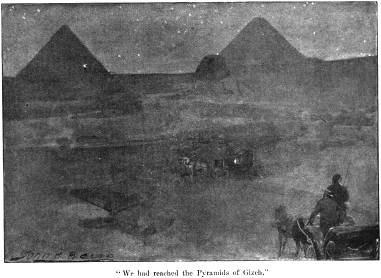

Although still shaded with Lebbek trees, the road no longer ran between human habitations, but far away on the right and left a few twinkling lights proclaimed the existence of Fellahin villages. Of foot-passengers we saw none, and save the occasional note of a night-bird, the howling of a dog in the far distance, and the rattle of our own wheels, scarcely a sound was to be heard. Gradually the road, which was raised several feet above the surrounding country, showed a tendency to ascend, and just as I was beginning to wonder what sort of a will-o'-the-wisp chase it was upon which I was being led, and what the upshot of it would be, it came to an abrupt standstill, and, towering into the starlight above me, I saw two things which swept away all my doubts, and told me, as plainly as any words could speak, that we were at the end of our journey. We had reached the Pyramids of Gizeh. As soon as I understood this, I signed to my driver to pull up, and, making him understand as best I could that he was to await my return, descended and made my way towards the Pyramids on foot.

Although still shaded with Lebbek trees, the road no longer ran between human habitations, but far away on the right and left a few twinkling lights proclaimed the existence of Fellahin villages. Of foot-passengers we saw none, and save the occasional note of a night-bird, the howling of a dog in the far distance, and the rattle of our own wheels, scarcely a sound was to be heard. Gradually the road, which was raised several feet above the surrounding country, showed a tendency to ascend, and just as I was beginning to wonder what sort of a will-o'-the-wisp chase it was upon which I was being led, and what the upshot of it would be, it came to an abrupt standstill, and, towering into the starlight above me, I saw two things which swept away all my doubts, and told me, as plainly as any words could speak, that we were at the end of our journey. We had reached the Pyramids of Gizeh. As soon as I understood this, I signed to my driver to pull up, and, making him understand as best I could that he was to await my return, descended and made my way towards the Pyramids on foot.

Keeping my eye on Pharos, whom I could see ahead of me, and taking care not to allow him to become aware that he was being followed, I began the long pull up to the plateau on which the largest of these giant monuments is situated. Fortunately for me the sand not only prevented any sound from reaching him, while its colour enabled me to keep him well in sight The road from the Mena House Hotel to the Great Pyramid is not a long one, but what it lacks in length it makes up in steepness. Never losing sight of Pharos for an instant, I ascended it. On arriving at the top, I noticed that he went straight forward to the base of the huge mass, and when he was sixty feet or so from it, called something in a loud voice. He had scarcely done so before a figure emerged from the shadow and approached him. Fearing they might see me, I laid myself down on the sands behind a large block of stone, whence I could watch them, remaining myself unseen.

As far as I could tell, the new-comer was undoubtedly an Arab, and, from the way in which he towered above Pharos, must have been a man of gigantic stature. For some minutes they remained in earnest conversation. Then, leaving the place where they had met, they went forward towards the great building, the side of which they presently commenced to climb. After a little they disappeared, and, feeling certain they had entered the Pyramid itself, I rose to my feet and determined to follow.

The Great Pyramid, as all the world knows, is composed of enormous blocks of granite, each about three feet high, and arranged after the fashion of enormous steps. The entrance to the passage which leads to the interior is on the thirteenth tier, and nearly fifty feet from the ground. With a feeling of awe which may be very well understood, when I reached it I paused before entering. I did not know on the threshold of what discovery I might be standing. And what was more, I reflected that if Pharos found me following him, my life would in all probability pay the forfeit. My curiosity, however, was greater than my judgment, and being determined, since I had come so far, not to go back without learning all there was to know, I hardened my heart, and, stooping down, entered the passage. When I say that it is less than four feet in height, and of but little more than the same width, and that for the first portion of the way the path slopes downwards at an angle of twenty-six degrees, some vague idea may be obtained of the unpleasant place it is. But if I go on to add that the journey had to be undertaken in total darkness, without any sort of knowledge of what lay before me, or whether I should ever be able to find my way out again, the foolhardiness of the undertaking will be even more apparent. Step by step, and with a caution which I can scarcely exaggerate, I made my way down the incline, trying every inch before I put my weight upon it, and feeling the walls carefully with either hand in order to make sure that no other passages branched off to right or left. After I had been advancing for what seemed an interminable period, but could not in reality have been more than five minutes, I found myself brought to a standstill by a solid wall of stone. For a moment I was at a loss how to proceed. Then I found that there was a turn in the passage, and the path, instead of continuing to descend, was beginning to work upwards, whereupon, still feeling my way as before, I continued my journey of exploration. The heat was stifling, and more than once foul things, that only could have been bats, flapped against my face and hands and sent a cold shudder flying over me. Had I dared for a moment to think of the immense quantity of stone that towered above me, or what my fate would be had a stone fallen from its place and blocked the path behind me, I believe I should have been lost for good and all. But, frightened as I was, a greater terror was in store for me.

After I had been proceeding for some time along the passage, I found that it was growing gradually higher. The air was cooler, and raising my head cautiously in order not to bump it against the ceiling, I discovered that I was able to stand upright. I lifted my hand, first a few inches, and then to the full extent of my arm; but the roof was still beyond my reach. I moved a little to my right in order to ascertain if I could touch the wall, and then to the left. But once more only air rewarded me. It was evident that I had left the passage and was standing in some large apartment; but, since I knew nothing of the interior of the Pyramid, I could not understand what it was or where it could be situated. Feeling convinced in my own mind that I had missed my way, since I had neither heard nor seen anything of Pharos, I turned round and set off in what I considered must be the direction of the wall; but though I walked step by step, once more feeling every inch of the way with my foot before I put it down, I seemed to have covered fifty yards before my knuckles came in contact with it. Having located it, I fumbled my way along it in the hope that I might discover the doorway through which I had entered; but though I tried for some considerable time, no sort of success rewarded me. I paused and tried to remember which way I had been facing when I made the discovery that I was no longer in the passage. In the dark, however, one way seemed like another, and I had turned myself about so many times that it was impossible to tell which was the original direction. Oh, how bitterly I repented having ever left the hotel! For all I knew to the contrary, I might have wandered into some subterranean chamber never visited by the Bedouins or tourists, whence my feeble cries for help would not be heard, and in which I might remain until death took pity on me and released me from my sufferings.

Fighting down the terror that had risen in my heart and threatened to annihilate me, I once more commenced my circuit of the walls, but again without success. I counted my steps backwards and forwards in the hope of locating my position. I went straight ahead on the chance of striking the doorway haphazard, but it was always with the same unsatisfactory result. Against my better judgment I endeavoured to convince myself that I was really in no danger, but it was useless. At last my fortitude gave way, a clammy sweat broke out upon my forehead, and remembering that Pharos was in the building, I shouted aloud to him for help. My voice rang and echoed in that ghastly chamber till the reiteration of it well-nigh drove me mad. I listened, but no answer came. Once more I called, but with the same result. At last, thoroughly beside myself with terror, I began to run aimlessly about the room in the dark, beating myself against the walls and all the time shouting at the top of my voice for assistance. Only when I had no longer strength to move, or voice to continue my appeals, did I cease, and falling upon the ground rocked myself to and fro in silent agony. Times out of number I cursed myself and my senseless stupidity in having left the hotel to follow Pharos. I had sworn to protect the woman I loved, and yet on the first opportunity I had ruined everything by behaving in this thoughtless fashion.

Once more I sprang to my feet, and once more I set off on my interminable search. This time I went more quietly to work, feeling my way carefully, and making a mental note of every indentation in the walls. Being unsuccessful, I commenced again, and once more scored a failure. Then the horrible silence, the death-like atmosphere, the flapping of the bats in the darkness, and the thought of the history and age of the place in which I was imprisoned, must have affected my brain, and for a space I believe I went mad. At any rate, I have a confused recollection of running round and round that loathsome place, and of at last falling exhausted upon the ground, firmly believing my last hour had come. Then my senses left me, and I became unconscious.

How long I remained in the condition I have just described, I cannot say. All I know is that, when I opened my eyes, I found the chamber bright with the light of torches, and no less a person than Pharos kneeling beside me. Behind him, but at a respectful distance, were a number of Arabs, and among them a man whose height could scarcely have been less than seven feet. This was evidently the individual who had met Pharos at the entrance to the Pyramid.

"Rise," said Pharos, addressing me, "and let this be a warning to you never to attempt to spy on me again. Think not that I was unaware that you were following me, or that the mistake on your part in taking the wrong turning in the passage was not ordained. The time has now gone by for me to speak to you in riddles; our comedy is at an end, and for the future you are my property, to do with as I please. You will have no will but my pleasure, no thought but to act as I shall tell you. Rise and follow me."

Having said this, he made a sign to the torch-bearers, who immediately led the way towards the door, which was now easy enough to find. Pharos followed them, and, more dead than alive, I came next, while the tall man I have mentioned brought up the rear. In this order we groped our way down the narrow passage. Then it was that I discovered the mistake I had made in entering. Whether by accident, or by the exercise of Pharos's will, as he had desired me to believe, it was plain I had taken the wrong turning, and, instead of going on to the King's Hall, where no doubt I should have found the man I was following, I had turned to the left, and had entered the apartment popularly, but erroneously, called the Queen's Chamber.

It would have been difficult to estimate the thankfulness I felt on reaching the open air once more. How sweet the cool night wind seemed after the close and suffocating atmosphere of the Pyramid, I cannot hope to make you understand. And yet, if I had only known, it would have been better for me, far better, had I never been found, and my life come to an end when I fell senseless upon the floor.

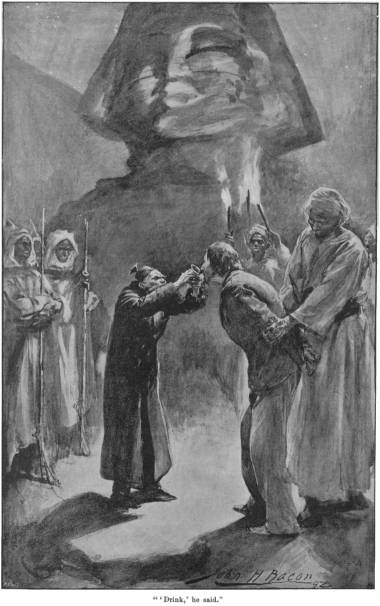

When we had left the passage and had clambered down to the sands once more, Pharos bade me follow him, and, leading the way round the base of the Pyramid, conducted me down the hill towards the Sphinx.

For fully thirty years I had looked forward to the moment when I should stand before this stupendous monument and try to read its riddle; but in my wildest dreams I had never thought to do so in such company. Looking down at me in the starlight, across the gulf of untold centuries, it seemed to smile disdainfully at my small woes.

"To-night," said Pharos, in that same extraordinary voice he had used a quarter of an hour before, when he bade me follow him, "you enter upon a new phase of your existence. Here, under the eyes of the Watcher of Harmachis, you shall learn something of the wisdom of the ancients."

At a signal, the tall man whom he had met at the foot of the Pyramid sprang forward and seized me by the arms from behind with a grip of iron. Then Pharos produced from his pocket a small case containing a bottle. From the latter he poured a few spoonfuls of some fluid into a silver cup, which he placed to my mouth.

At a signal, the tall man whom he had met at the foot of the Pyramid sprang forward and seized me by the arms from behind with a grip of iron. Then Pharos produced from his pocket a small case containing a bottle. From the latter he poured a few spoonfuls of some fluid into a silver cup, which he placed to my mouth.

"Drink," he said.

At any other time I should have refused to have complied with such a request; but on this occasion so completely had I fallen under his influence that I was powerless to disobey.

The opiate, or whatever it was, must have been a powerful one, for I had scarcely swallowed it before an attack of giddiness seized me. The outline of the Sphinx and the black bulk of the Great Pyramid beyond was merged in the general darkness. I could hear the wind of the desert singing in my ears, and the voice of Pharos muttering something in an unknown tongue beside me. After that I sank down on the sand, and presently became oblivious of everything.

How long I remained asleep I have no idea. All I know is, that with a suddenness that was almost startling, I found myself awake and standing in a crowded street. The sun shone brilliantly, and the air was soft and warm. Magnificent buildings, of an architecture that my studies had long since made me familiar with, lined it on either hand, while in the roadway were many chariots and gorgeously furnished litters, before and beside which ran slaves, crying aloud in their masters' names for room.

From the position of the sun in the sky, I gathered that it must be close upon mid-day. The crowd was momentarily increasing, and as I walked, marvelling at the beauty of the buildings, I was jostled to and fro, and oftentimes called upon to stand aside. That something unusual had happened to account for this excitement was easily seen, but what it was, being a stranger, I had no idea. Sounds of wailing greeted me on every side, and in all the faces upon which I looked signs of overwhelming sorrow were to be seen.

Suddenly a murmur of astonishment and anger ran through the crowd, which separated hurriedly to right and left. A moment later a man came through the lane thus formed. He was short and curiously misshapen, and, as he walked, he covered his face with the sleeve of his robe, as though he were stricken with grief or shame.

Turning to a man who stood beside me, and who seemed even more excited than his neighbours, I inquired who the new-comer might be.

"Who art thou, stranger?" he answered, turning sharply on me. "And whence comest thou that thou knowest not Ptahmes, Chief of the King's Magicians? Learn, then, that he hath fallen from his high estate, inasmuch as he made oath before Pharaoh that the firstborn of the King should take no hurt from the spell this Israelitish sorcerer, Moses, hath cast upon the land. Now the child and all the firstborn of Egypt are dead, and the heart of Pharaoh being hardened against his servant, he hath shamed him, and driven him from before his face."

As he finished speaking, the disgraced man withdrew his robe from his face, and I realized the astounding fact that Ptahmes the Magician and Pharos the Egyptian were not ancestor and descendant, but one and the same person!

CHAPTER XI.

OF the circumstances under which my senses returned to me after the remarkable vision—for that is the only name I can assign to it—which I have described in the preceding chapter, not the vaguest recollection remains to me.

When Pharos bade me drink the stuff he had poured out, we were standing before the Sphinx at Gizeh; now, when I opened my eyes, I was back once more in my bedroom at the hotel in Cairo. Brilliant sunshine was streaming in through the jalousies, and I could hear the sound of footsteps in the corridor outside. At first I felt inclined to treat the whole as a dream,—not a very pleasant one, it is true,—but the marks upon my hands, made when I had beaten them on the rough walls of that terrible chamber in the Pyramid, soon showed me the futility of so doing. I remembered how I had run round and round that dreadful place in search of a way out, and the horror of the recollection was sufficient to bring a cold sweat out once more upon my forehead. Strange to say, I mean strange in the light of all that has transpired since, the memory of the threat Pharos had used to me caused me no uneasiness, and yet, permeating my whole being, there was a loathing for him and a haunting fear that was beyond description in words.

Indeed, I cannot hope to make you understand the light in which this man figured to me. In other and more ordinary phases of life the hatred one entertains for a man is usually of a less passive nature. One either shuns his society outright, or, if compelled to associate with him, makes a point of letting him see that unless he changes his behaviour and withdraws the cause of offence, it will, in all likelihood, lead him into trouble. With Pharos, however, the case was different. The dislike I felt for him was the outcome, not so much of a physical animosity, if I may so designate it, as of a peculiar description of supernatural fear. Reason with myself as I would, I could not get rid of the belief that the man was more than he pretended to be, that there was some link between him and the Unseen World which it was impossible for me to understand, and arguing with myself in this way, I was the more disposed to believe in the vision of the preceding night.

On consulting my watch, I was amazed to find that it wanted only a few minutes of ten o'clock. I sprang from my bed, and a moment later came within an ace of measuring my length upon the floor. What occasioned this weakness I could not tell, but the fact remains that I was as feeble as if I had been confined to my bed for six months. The room spun round and round, until I became so giddy that I was compelled to clutch at a table for support. What was stranger, as soon as I stood upon my feet, I was conscious of a sharp pricking sensation on my left arm, a little above the elbow; indeed, so sharp was it, that it could be felt, not only on the tips of my fingers, but for some distance down my side. To examine the place was the work of a moment. On the fleshy part of the arm, three inches or so above the elbow, was a small spot, such as might have been made by some sharp-pointed instrument—a hypodermic syringe, for instance—and which was fast changing from a pale pink to a purple hue. Seating myself on my bed, I examined it carefully. My wonderment was increased when I discovered that the spot itself, and the flesh surrounding it for a distance of more than an inch, was to all intents and purposes incapable of sensation. I puzzled my brains in vain to account for its presence there. I did not remember scratching myself with anything in my room, nor could I discover that the coat I had worn on the preceding evening showed any signs of a puncture.

After a few moments the feeling of weakness which had seized me when I first left my bed wore off. I accordingly dressed myself with as much despatch as I could put into the operation, and my toilet being completed, left my room and went in search of the Fräulein Valerie. To my disappointment, she was not visible. I, however, discovered Pharos seated in the verandah, in the full glare of the morning sun, with the monkey, Pehtes, on his knee. For once he was in the very best of tempers. Indeed, since I had first made his acquaintance, I had never known him so merry. At a sign, I seated myself beside him.

"My friend," he began, "I am rejoiced to see you. Permit me to inform you that you had a narrow escape last night. However, since you are up and about this morning, I presume you are feeling none the worse for it."

I described the fit of vertigo that had overtaken me when I rose from my bed, and went on to question him as to what had happened after I had become unconscious on the preceding night.

"I can assure you, you came very near being a lost man," he answered. "As good luck had it, I had not left the Pyramid, and so heard you cry for help, otherwise you might be in the Queen's Hall at this minute. You were quite unconscious when we found you, and you had not recovered by the time we reached home again."

"Not recovered?" I cried in amazement. "But I walked out of the Pyramid unassisted, and accompanied you across the sands to the Sphinx, where you gave me something to drink and made me see a vision."

Pharos gazed incredulously at me.

"My dear fellow, you must have dreamt it," he said. "After all you had gone through, it is scarcely likely I should have permitted you to walk, while as for the vision you speak of—well, I must leave that to your own common sense. If necessary, my servants will testify to the difficulty we experienced in getting you out of the Pyramid, while the very fact that you yourself have no recollection of the homeward journey would help to corroborate what I say."

This was all very plausible; at the same time I was far from being convinced. I knew my man too well by this time to believe that because he denied any knowledge of the circumstance in question he was really as innocent as he was anxious I should think him. The impression the vision—for, as I have said, I shall always call it by that name—had made upon me was still clear and distinct in my mind. I closed my eyes and once more saw the street filled with that strangely-dressed crowd, which drew back on either hand to make a way for the disgraced Magician to pass through. It was all so real, and yet, as I was compelled to confess, so improbable, that I scarcely knew what to think. Before I could come to any satisfactory decision, Pharos turned to me again.

"Whatever your condition last night may have been," he said, "it is plain you are better this morning, and I am rejoiced to see it, for the reason I have made arrangements to complete the business which has brought us here. Had you not been well enough to travel, I should have been compelled to leave you behind."

I searched his face for an explanation.

"The mummy?" I asked.

"Exactly," he replied. "The mummy. We leave Cairo this afternoon for Luxor. I have made the necessary arrangements, and we join the steamer at mid-day,—that is to say, in about two hours' time."

Possibly it was this preparation to complete the work he had come to do, by replacing the mummy of the King's Magician in the tomb in which it had lain for so many thousand years, and from which my father had taken it, that had put him in such a good humour. At any rate, never since I had known him had I found him so amiable as on this particular occasion. I inquired after the Fräulein Valerie, whom I had not yet seen, whereupon Pharos informed me that she had gone to her room to prepare for the excursion up the Nile.

And now, Mr. Forrester," he said, rising from his chair and returning the monkey to his place of shelter in the breast of his coat, "if I were you, I should follow her example. It will be necessary for us to start as punctually as possible."

Sharp on the stroke of twelve a carriage made its appearance at the door of the hotel. The Fräulein Valerie, Pharos, and myself took our places in it, the gigantic Arab whom I had seen at the Pyramid on the preceding night, and who I was quite certain had held my arms when Pharos compelled me to drink the potion before the Sphinx, took his place beside the driver, and we set off along the road to Bulak en route to the Embabeh. Having reached this, one of the most characteristic spots in Cairo, we made our way along the bank towards a landing-stage, beside which a handsome steamer was moored. If anything had been wanting in my mind to convince me of the respect felt for Pharos by such Arabs as he was brought in contact with, I should have found it in the behaviour of the crew of this vessel. Had he been imbued with the powers of life and death, they could scarcely have stood in greater awe of him.

Our party being on board, there was no occasion for any further delay; consequently, as soon as we had reached the upper deck, the ropes were cast off, and with prodigious fuss the steamer made her way out into mid-stream, and began the voyage which was destined to end in such a strange fashion, not for one alone, but indeed for all our party.

Full as my life had been of extraordinary circumstances during the last few weeks, I am not certain that my feelings as I stood upon the deck of the steamer, while she made her way up stream, past the Khedive's Palace, the Kasr-en-Nil barracks, Kasr-el-Ain, the Island of Rodah, and Gizeh, did not eclipse them. Our vessel was in every way a luxurious one, and to charter her must have cost Pharos a pretty penny. Immediately we got under weigh, the latter departed to his cabin, while the Fräulein Valerie and I stood side by side under the awning, watching the fast-changing landscape, but scarcely speaking. The day was hot, with scarcely a breath of wind to cool the air. Ever since the first week in June the Nile had been slowly rising, and was now running, a swift and muddy river, only a few feet below the level of her banks. I looked at my companion, and, as I did so, thought of all that we had been through together in the short time we had known each other. Less than a month before, Pharos and I had to all intents and purposes been strangers, and Valerie and I had not met at all. Then I had travelled with them to Egypt, and was now embarking on a voyage up the Nile in their company, and for what purpose? To restore the body of Merenptah's Chief Magician to the tomb from which it had been taken by my own father nearly twenty years before. Could anything have seemed more unlikely, and yet could anything have been more true? Amiable as were my relations with my host at present, there was a feeling deep down in my heart that troublous times lay ahead of us. The explanation Pharos had given me of what had occurred on the preceding night had been plausible enough, as I have said, and yet I was far from being convinced by it. There were only two things open to me to believe. Either he had stood over me saying, "For the future you are mine to do with as I please. You will have no will but my pleasure, no thought but to act as I shall tell you," or I had dreamt it. When I had taxed him with it some hours before, he had laughed at me, and had told me to attribute it all to the excited condition of my brain. But the feeling of reality with which it had inspired me was, I felt sure, too strong for it to have been imaginary; and yet, do what I would, I could not throw off the unpleasant belief that, however much I might attempt to delude myself to the contrary, I was in reality more deeply in his power than I fancied myself to be.

One thing struck me most forcibly, and that was the fact that, now we were away from Cairo, the Fräulein Valerie was in better spirits than I had yet seen her. Glad as I was, however, to find her happier, the knowledge of her cheerfulness, for some reason or another, chilled and even disappointed me. Yet, Heaven knows, had I been asked, I must have confessed that I should have been even more miserable had she been unhappy. When I joined them at lunch, I was convinced that I was a discordant note. I was thoroughly out of humour, not only with myself, but with the world in general, and the fit had not left me when I made my way up to the deck again.

Downcast as I was, however, I could not repress an exclamation of pleasure at the scene I saw before me when I reached it. In the afternoon light the view, usually so uninviting, was picturesque in the extreme. Palm groves decorated either bank, with here and there an Arab village peering from among them; while, as if to afford a fitting background, in the distance could be seen the faint outline of the Libyan Hills. At any other time I should have been unable to contain myself until I had made a sketch of it; now, however, while it impressed me with its beauty, it only served to remind me of the association in which I found myself. The centre of the promenade deck, immediately abaft the funnel, was arranged somewhat in the fashion of a sitting-room, with a carpet, easy-chairs, a sofa, and corresponding luxuries. I seated myself in one of the chairs, and was still idly watching the country through which we were passing, when Pharos made his appearance from below, carrying the monkey, Pehtes, in his arms, and seated himself beside me. It was plain that he was still in a contented frame of mind, and his opening speech, when he addressed me, showed that he had no intention of permitting me to be in anything else.

"My dear Forrester," he said in what was intended to be a conciliatory tone, "I feel sure you have something upon your mind that is worrying you. Is it possible you are still brooding over what you said to me this morning? Remember you are my guest, therefore I am responsible for your happiness. I cannot permit you to wear such an expression of melancholy. Pray tell me your trouble, and if I can help you in any way, rest assured I shall be only too glad to do so."

"I am afraid, after the explanation you gave me this morning, that it is impossible for you to help me," I answered. "To tell you the truth, I have been worrying over what happened last night, and the more I think of it, the less able I am to understand it."

"What is it you find difficult to understand?" he inquired. "I thought we were agreed on the subject: when we spoke of it this morning."

"Not as far as I am concerned," I replied. "And if you consider for a moment, I fancy you will understand why. As I told you then, I have the best possible recollection of all that befell me in the Pyramid, and of the fright I sustained in that terrible room. I remember your coming to my assistance, and I am as convinced that, when my senses returned to me, I followed you down the passage, out into the open air, and across the sands to a spot before the Sphinx, where you gave me some concoction to drink, as I am that I am now sitting on this deck beside you."

"And I assure you with equal sincerity that it is all a delusion," the old man replied. "You must have dreamt the whole thing. Now I come to think of it, I do remember that you said something about a vision which I enabled you to see. Perhaps, as your memory is so keen on the subject, you may be able to give me some idea of its nature."

I accordingly described what I had seen. From the way he hung upon, my words, it was evident that the subject interested him more than he cared to confess. Indeed, when I had finished, he gave a little gasp that was plainly one of relief, though why he should have been so I could not understand.

"And the man you saw coming through the crowd, this Ptahmes, what was he like? Did you recognise him? Should you know his face again?"

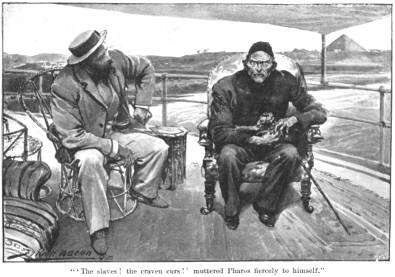

"I scarcely know how to tell you," I answered diffidently, a doubt as to whether I had really seen the vision I had described coming over me for the first time, now that I was brought face to face with the assertion I was about to make. "It seems so impossible, and I am weak enough to feel that I should not like you to think I am jesting. The truth of the matter is, the face of the disgraced Magician was none other than your own. You were Ptahmes, the man who walked with his face covered with his mantle, and before whom the crowd drew back as if they feared him, and yet hated him the more because they did so."

"The slaves, the craven curs," muttered Pharos fiercely to himself, oblivious of my presence, his sunken eyes looking out across the water, but I am convinced seeing nothing. "So long as he was successful they sang his praises through the city, but when he failed and was cast out from before Pharaoh, there were only six in all the country brave enough to declare themselves his friends."

"The slaves, the craven curs," muttered Pharos fiercely to himself, oblivious of my presence, his sunken eyes looking out across the water, but I am convinced seeing nothing. "So long as he was successful they sang his praises through the city, but when he failed and was cast out from before Pharaoh, there were only six in all the country brave enough to declare themselves his friends."

Then, recollecting himself, he turned to me, and with one of his peculiar laughs, to which I had by this time grown accustomed, he continued, "But there, if I talk like this, you will begin to imagine that I really have some association with my long-deceased relative, the man of whom we are speaking, and whose mummy is in the cabin yonder. Your account of the vision, if by that name you still persist in calling it, is extremely interesting, and goes another step towards proving how liable the human brain is, under stress of great excitement, to seize upon the most unlikely stories, and even to invest them with the necessary mise-en-scène. Now I'll be bound you could reproduce the whole picture, were such a thing necessary — the buildings, the chariots, the dresses, nay, even the very faces of the crowd."

"I am quite sure I could," I answered, filled with a sudden excitement at the idea, "and what is more, I will do so. So vivid was the impression it made upon my mind that not a detail has escaped my memory. Indeed, I really believe it will be found that a large proportion of the things I saw then I had never seen or heard of before. This, I think, should go some way towards proving whether or not my story is the fallacy you suppose."

"You mistake me, my dear Forrester," he hastened to reply. "I do not go so far as to declare it to be altogether a fallacy; I simply say that what you think you saw must have been the effect of the fright you received in the Pyramid. But your idea of painting the picture is distinctly a good one, and I shall look forward with pleasure to giving you my opinion upon it when it is finished. As you are well aware, I am a fair Egyptologist, and I have no doubt I shall be able to detect any error in the composition, should one exist."

"I will obtain my materials from my cabin, and set to work at once," I said, rising from my chair, "and when I have finished you shall certainly give me your opinion on it."

As on a similar occasion already described, under the influence of my enthusiasm the feeling of animosity I usually entertained towards him left me entirely. I went to my cabin, found the things I wanted, and returned with them to the deck. When I reached it, I found the Fräulein Valerie there. She was dressed in white from head to foot, and was slowly fanning herself with the same large ostrich feather fan which I remembered to have seen her using on that eventful night when I had dined with Pharos in Naples. Her left hand was hanging by her side, and as I greeted her and reseated myself in my chair, I could not help noticing its whiteness and exquisite proportions.

"Mr. Forrester was fortunate enough to be honoured by a somewhat extraordinary dream last night," said Pharos by way of accounting for my sketching materials. "The subject was Egyptian, and I have induced him to try and make a picture of the scene for my especial benefit."

"Do you feel equal to the task?" Valerie inquired, with unusual interest as I thought. "Surely it must be very difficult. As a rule, even the most vivid dreams are so hard to remember in detail."

"This was something more than a dream," I answered confidently, "as I shall presently demonstrate to Monsieur Pharos. Before I begin, however, I am going to make one stipulation."

"And what is that?" asked Pharos.

"That while I am at work you tell us, as far as you know it, the history of Ptahmes, the King's Magician. Not only does it bear upon the subject of my picture, but it is fit and proper, since we have his mummy on board, that we should know more than we do at present of our illustrious fellow-traveller."

Pharos glanced sharply at me, as if he were desirous of discovering whether any covert allusion was contained in my speech. I flatter myself, however, that my face told him nothing.

"What could be fairer?" he said, after a slight pause. "While you paint I will tell you all I know, and since he is my ancestor, and I have made his life my especial study, it may be supposed I am acquainted with as much of his history as research has been able to bring to light. Ptahmes, or, as his name signifies, the man beloved of Ptah, was the son of Netruhôtep, a Priest of the High Temple of Ammon, and a favourite of Rameses II. From the moment of his birth great things were expected of him, for, by the favour of the gods, he was curiously misshapen, and it is well known that those whom the mighty ones punish in one way usually have it made up to them in another. It is just possible that it may be from him I inherit my own un-pleasing exterior. However, to return to Ptahmes, whose life, I can assure you, forms an interesting study. At an early age the boy showed an extraordinary partiality for the mystic, and it was doubtless this circumstance that induced his father to entrust him to the care of the Chief Magician, Haper, a wise man, by whom the lad was brought up. Proud of his calling, and imbued with a love for the sacred rites, it is small wonder that he soon outdistanced those with whom he was brought in contact. So rapid, indeed, were the strides he made that the news of his attainments at length came to the ears of Pharaoh. He was summoned to the royal presence, and commanded to give an exhibition of his powers. So pleased was the King at the result that he ordered him to remain at Court, and to be constantly in attendance upon his person. From this point the youth's career was assured. Year by year, and step by step, he made his way up the ladder of fame till he became a mighty man in the land, a councillor, Prophet of the North and South, and Chief of the King's Magicians. Then, out of the land of Midian rose the star that, as it had been written, should cross his path and bring about his downfall. This was the Israelite Moses, who came into Egypt and set himself up against Pharaoh, using magic the like of which had never before been seen. But that portion of the story is too well known to bear repetition. Let it suffice that Pharaoh called together his councillors, the principal of whom was Ptahmes, now a man of mature years, and consulted with them. Ptahmes, scenting a rival in this Hebrew, and foreseeing the inevitable result, was for acceding to the request he made, and letting the Israelites depart in peace from the kingdom. To this course, however, Pharaoh would not agree, and at the same time he allowed his favourite to understand that, not only was such advice the reverse of palatable, but that a repetition of it would in all probability deprive him of the royal favour. Once more the Hebrews appeared before Pharaoh and gave evidence of their powers, speaking openly to the King and using threats of vengeance in the event of their demands not being acceded to. But Pharaoh was stiff-necked and refused to listen, and in consequence evil days descended upon Egypt. By the magic of Moses the fish died, and the waters of the Nile were polluted so that the people could not drink; frogs, in such numbers as had never been seen before, made their appearance and covered the whole face of the land. Then Pharaoh called upon Ptahmes and his Magicians, and bade them imitate all that the others had done. And the Magicians did so, and by their arts frogs came up out of the land, even as Moses had made them do. Seeing this, Pharaoh laughed the Israelites to scorn, and once more refused to consider their request. Whereupon plagues of lice, flies, and boils, which broke out upon man and beast, mighty storms, and a great darkness in which no man could see another's face, fell upon the Egyptians. Once more Pharaoh, whose heart was still hardened against Moses, called Ptahmes to his presence, and bade him advise him as to the course he should pursue. Being already at war with his neighbours, he had no desire to permit this horde to cross his borders only to take sides with his enemies against him. And yet to keep them and to risk further punishment was equally dangerous. Moses was a stern man, and, as the King had had already good reason to know, was not one to be trifled with. Only that morning he had demanded an audience, and had threatened Pharaoh with a pestilence that should cause the death of every first-born son throughout the land if he still persisted in his refusal.

"Now Ptahmes, who, as I have said, was an astute man, and who had already been allowed to see the consequences of giving advice that did not tally with his master's humour, found himself in a position, not only of difficulty, but also of some danger. Either he must declare himself openly in favour of letting the Hebrews go, and once more run the risk of Pharaoh's anger and possible loss of favour, or he must side with his master, and, having done so, put forth every effort to prevent the punishment Moses had decreed. After hours of suspense and overwhelming anxiety, he adopted the latter course. Having taken counsel with his fellow Magicians, he assured Pharaoh, on the honour of the gods, that what the Israelite had predicted could never come to pass. Fortified with this promise, Pharaoh once more refused to permit the strangers to leave the land. As a result, the first-born son of the King, the child whom he loved better even than his kingdom, sickened of a mysterious disease and died that night, as did the first-born of all the Egyptians, rich and poor alike. In the words of your own Bible, 'There was a great cry in Egypt; for there was not a house where there was not one dead.' Then Pharaoh's hatred was bitter against his advisers, and he determined that Ptahmes in particular should die. He sought him with the intention of killing him, but the Magician had received timely warning and had escaped into the mountains, where he hid himself for many months. Little by little the strain upon his health gave way, he grew gradually weaker, and in the fiftieth year of his life Osiris claimed him for his own. It was said at the time that for the sin he had caused Pharaoh to do, and the misery he had brought upon the land of Egypt, and swearing falsely in the name of the gods, he had been cursed with perpetual life. This, however, could not have been so, seeing that he died in the mountains and that his mummy was buried in the tomb whence your father took it. Such is the story of Ptahmes, the beloved of Ptah, son of Netruhôtep, Chief of the Magicians and Prophet of the North and South."

CHAPTER XII.

STRANGE as it may seem, when all the circumstances attending it are taken into consideration, I am compelled to confess, in looking back upon it now, that that voyage up the Nile was one of the most enjoyable I have ever undertaken. It is true, the weather was somewhat warmer than was altogether agreeable; but if you visit Egypt at midsummer, you must be prepared for a little discomfort in that respect. From the moment of rising until it was time to retire to rest at night, our time was spent under the awning on deck, reading, conversing, and watching the scenery on either bank, and on my part in putting the finishing touches to the picture I had commenced the afternoon we left Cairo.

When it was completed to my satisfaction, which was on the seventh day of our voyage, and that upon which we expected to reach Luxor, I showed it to Pharos. He examined it carefully, and it was some time before he offered an opinion upon it

"I will pay you the compliment of saying I consider it a striking example of your art," he said, when he did speak. "At the same time, I must confess it puzzles me. I do not understand whence you drew your inspiration. There are things in this picture, important details in the dress and architecture, that I feel certain have never been seen or dreamt of by this century. How, therefore, you could have known them passes my comprehension."

"I have already told you that that picture represents what I saw in my vision," I answered.

"So you still believe you saw a vision?" he asked, with a return to his old sneering habit, as he picked the monkey up and began to stroke his ears.

"I shall always do so," I answered. "Nothing will ever shake my belief in that."

At this moment the Fräulein Valerie joined us, whereupon Pharos handed her the picture and asked for her opinion upon it. She looked at it steadfastly, while I waited with some anxiety for her criticism.

"It is very clever," she said, still looking at it, "and beautifully painted; but, if you will let me say so, I do not know that I altogether like it. There is something about it that I do not understand. And see, you have given the central figure Monsieur Pharos's face."

She looked up from the picture at me as if to inquire the reason of this likeness, after which we both glanced at Pharos, who was seated before us, wrapped as usual in his heavy rug, with the monkey, Pehtes, looking out from his invariable hiding-place beneath his master's coat. For the moment I did not know what answer to return. To have told her in the broad light of day, with the prosaic mud banks of the Nile on either hand, and the Egyptian sailors washing paint-work at the farther end of the deck, that in my vision I had been convinced that Pharos and Ptahmes were one and the same person, would have been too absurd. Pharos, however, relieved me of the necessity of my saying anything by replying for me.

"Mr. Forrester has done me great honour, my dear," he said gaily, "in choosing my features for the central figure. I had no idea before that my unfortunate person was capable of such dramatic effect. But now to more serious business. If at any time, Forrester, you should desire to dispose of that picture, I shall be delighted to take it off your hands."

"You may have it now," I answered. "If you think it worthy of your acceptance, I will gladly give it you. To tell the truth, I myself, like the Fräulein here, am a little frightened of it, though why I should be, seeing that it is my own work, Heaven only knows."

"As you say, Heaven only knows," returned Pharos solemnly, and then making the excuse that he would out the picture in a place of safety, he left us and went to his cabin, Pehtes hopping along the deck behind him.

For some time after he had left us the Fräulein and I sat silent. The afternoon was breathless, and even our progress through the water raised no breeze. At the time we were passing the town of Keneh, a miserable collection of buildings of the usual Nile type, and famous only as being a rallying place for Mecca pilgrims, and for the Kulal and Ballas (water bottles), which bear its name.

While her eyes were fixed upon it, I was permitted an opportunity of studying my companion's countenance. I noted the proud poise of her head, the beauty of her face, and the luxuriance of the hair coiled so gracefully above it. She was a queen among women, as I had so often told myself; one whom any man might be proud to love, and then I added, as another thought struck me, one for whom the man she loved would willingly lay down his life to save. That I loved her with a sincerity and devotion greater than I had ever felt for any other human being, I was fully aware by this time. If the truth must be told, I believe I had loved her from the moment I first saw her face. But was it possible that she could love me? That was for time to show.

"I have noticed that you are very thoughtful to-day, Fräulein," I said, as the steamer dropped the town behind her and continued her journey up stream in a more westerly direction.

"Have I not good reason to be?" she answered. "You must remember I have made this journey before."

"But why should that fact produce such an effect upon you?" I asked. "To me it is a pleasure that has not yet begun to pall, and as you will, I am sure, admit, Pharos has proved a most thoughtful and charming host."

I said this with intention, for I wanted to see what reply she would make.

"I have not noticed his behaviour," she answered wearily. "It is always the same to me. But I do know this, that after each visit to the place for which we are now bound, great trouble has resulted for some one. Heaven grant it may not be so on this occasion."

"I do not see what trouble can result," I said. "Pharos is simply going to replace the mummy in the tomb from which it was taken, and after that I presume we shall return to Cairo, and probably to Europe."

"And then?"

"After that—"

But I could get no farther. The knowledge that in all likelihood as soon as we reached Europe I should have to bid her good-bye and return to London was too much for me, and for this reason I came within an ace of blurting out the words that were in my heart. Fortunately, however, I was able to summon up my presence of mind in time to avert such a catastrophe, otherwise I cannot say what the result would have been. Had I revealed my love to her and asked her to be my wife and she had refused me, our position, boxed up together as we were on board the steamer, and with no immediate prospect of release, would have been uncomfortable in the extreme. So I crammed the words back into my heart, and waited for another and more favourable opportunity.

The sun was sinking behind the Arabian hills, in a wealth of gold and crimson colouring, as we obtained our first glimpse of the mighty ruins we had come so far to see. Out of a dark green sea of palms to the left rose the giant pylons of the Temple of Ammon at Karnak. A few minutes later Luxor itself was visible, and within a quarter of an hour our destination was reached, and the steamer was at a standstill.

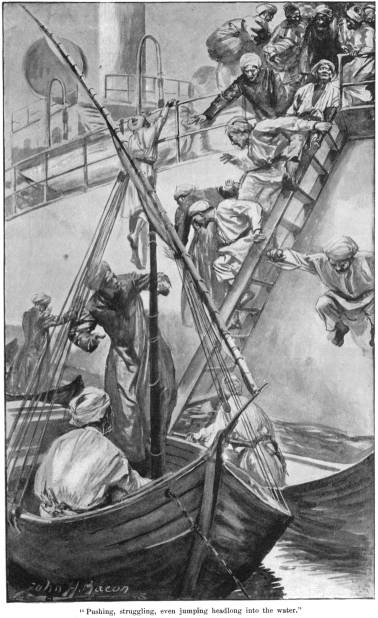

We had scarcely come to an anchor before the vessel was surrounded by small boats, the occupants of which clambered aboard, despite the efforts of the officers and crew to prevent them. As usual, they brought with them spurious relics of every possible sort and description, not one of which, however, our party could be induced to buy. The Fräulein Valerie and I were still protesting when Pharos emerged from his cabin and approached us. Never shall I forget the change that came over the scene. From the expressions upon the rascals' faces as they recognised him, I gathered that he was well known to them; at any rate, within five seconds of his appearance, not one of our previous persecutors remained aboard the vessel. Pushing, struggling, even jumping headlong into the water, they made their way over the side.

We had scarcely come to an anchor before the vessel was surrounded by small boats, the occupants of which clambered aboard, despite the efforts of the officers and crew to prevent them. As usual, they brought with them spurious relics of every possible sort and description, not one of which, however, our party could be induced to buy. The Fräulein Valerie and I were still protesting when Pharos emerged from his cabin and approached us. Never shall I forget the change that came over the scene. From the expressions upon the rascals' faces as they recognised him, I gathered that he was well known to them; at any rate, within five seconds of his appearance, not one of our previous persecutors remained aboard the vessel. Pushing, struggling, even jumping headlong into the water, they made their way over the side.

"They seem to know you," I said to Pharos, with a laugh, as the last of the gang took a header from the fail into the water.

"They do," he answered grimly. "I think I can safely promise you that, after this, not a man in Luxor will willingly set foot upon this vessel, not for all the wealth of Egypt. Would you care to try the experiment?"

"Very much," I said, and taking an Egyptian pound piece from my pocket, I stepped to the side and invited the rabble to come aboard and claim it. But the respect they entertained for Pharos was evidently greater than their love of gold, at any rate not a man seemed inclined to venture.

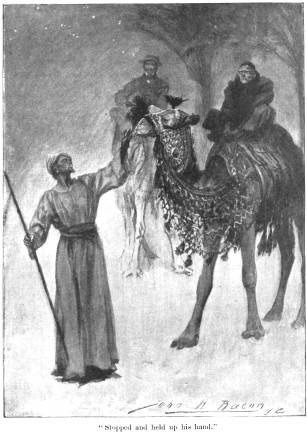

"A fair test," said Pharos. "You may rest assured that, unless you throw it over to them, your money will remain in your own pocket. But see, some one of importance is coming off to us. I am expecting a messenger, and in all probability it is he."

A somewhat better boat than those clustered around us was putting off from the bank, and seated in her was an Arab, clad in white bernouse and wearing a black turban upon his head.

"Yes, it is he," said Pharos, as with a few strokes of their oars the boatmen brought their craft alongside.

Before I could inquire who the person might be whom he was expecting, the man I have just described had reached the deck, and, after looking about him, had approached the spot where Pharos was standing. Accustomed as I was to the deference shown by the Arabs towards their superiors, of whose rank they were aware, I was far from expecting the exhibition of servility I now beheld. So overpowered was the newcomer by the reverence he felt for Pharos, that he could scarcely stand upright.

"I expected thee, Salem Awad," said Pharos, in Arabic. "What tidings dost thou bring?"

"It was to tell thee," the man replied, "that he whom thou didst order to be here has heard of thy coming, and will await thee at the place of which thou hast spoken."

"It is well," continued Pharos, "and I am pleased, Has all that I wrote to thee of been prepared?"

"All has been prepared and awaits thy coming."

"Return, then, and tell him who sent thee to me that I will be with him before he sleeps to-night."

The man bowed once more and made his way to his boat, in which he departed for the bank.

When he had gone, Pharos turned to me.

"We are expected," he said, "and, as you heard him say, preparations have been made to enable us to carry out the work we have come to do. After all his journeying, Ptahmes has at last returned to the city of his birth I and death. It is a strange thought, is it not? Look about you, Mr. Forrester, and remember that you are among the mightiest ruins the world has known. Yonder is the Temple of Luxor, away to the north you can see the remains of the Temple of Ammon at Karnak, both of which, five thousand years ago, were connected by a mighty road. On the west bank is the Necropolis of Thebes, with the tombs that once contained the mortal remains of the mighty ones of Egypt. Where are those mighty ones now? Scattered to the uttermost parts of the earth, stolen from their resting-places to adorn glass cases in European museums, and to be sold by auction by Jew salesmen at so much per head, according to their dates and state of preservation. But there! time is too short to talk of such indignity. The gods will avenge it in their own good time. Let it suffice that to-night we shall fulfil our errand. Am I right in presuming that you desire to accompany me?"